Key facts

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive life-threatening lung disease that causes breathlessness (initially with exertion) and predisposes to exacerbations and serious illness.

- The Global Burden of Disease Study reports a prevalence of 251 million cases of COPD globally in 2016.

- Globally, it is estimated that 3.17 million deaths were caused by the disease in 2015 (that is, 5% of all deaths globally in that year).

- More than 90% of COPD deaths occur in low and middle-income countries.

- The primary cause of COPD is exposure to tobacco smoke (either active smoking or secondhand smoke).

- Other risk factors include exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution and occupational dusts and fumes.

- Exposure to indoor air pollution can affect the unborn child and represent a risk factor for developing COPD later in life.

- Some cases of COPD are due to long-term asthma.

- COPD is likely to increase in coming years due to higher smoking prevalence and aging populations in many countries.

- Many cases of COPD are preventable by avoidance or early cessation of smoking. Hence, it is important that countries adopt the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC) and implement the MPOWER package of measures so that non-smoking becomes the norm globally.

- COPD is not curable, but treatment can relieve symptoms, improve quality of life and reduce the risk of death.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disease state characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. This newest definition of COPD, provided by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, provides a broad description that better explains this disorder and its signs and symptoms (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2001).

While previous definitions have included emphysema and chronic bronchitis under the umbrella classification of COPD, this was often confusing because most patients with COPD present with overlapping signs and symptoms of these two distinct disease processes.

COPD may include diseases that cause airflow obstruction (eg, emphysema, chronic bronchitis) or a combination of these disorders. Other diseases such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and asthma were previously classified as types of chronic obstructive lung disease. However, asthma is now considered a separate disorder and is classified as an abnormal airway condition characterized primarily by reversible inflammation. COPD can coexist with asthma. Both of these diseases have the same major symptoms; however, symptoms are generally more variable in asthma than in COPD.

People with COPD commonly become symptomatic during the middle adult years, and the incidence of COPD increases with age. Although certain aspects of lung function normally decrease with age (eg, vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]), COPD accentuates and accelerates these physiologic changes.

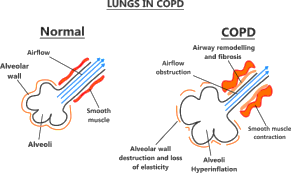

Pathophysiology

In COPD, the airflow limitation is both progressive and associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to noxious particles or gases. The inflammatory response occurs throughout the airways, parenchyma, and pulmonary vasculature (NIH, 2001). Because of the chronic inflammation and the body’s attempts to repair it, narrowing occurs in the small peripheral airways. Over time, this injury-and-repair process causes scar tissue formation and narrowing of the airway lumen. Airflow obstruction may also be due to parenchymal destruction as seen with emphysema, a disease of the alveoli or gas exchange units.

In addition to inflammation, processes relating to imbalances of proteinases and antiproteinases in the lung may be responsible for airflow limitation. When activated by chronic inflammation, proteinases and other substances may be released, damaging the parenchyma of the lung. The parenchymal changes may also be consequences of inflammation, environmental, or genetic factors (eg, alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Early in the course of COPD, the inflammatory response causes pulmonary vasculature changes that are characterized by thickening of the vessel wall. These changes may occur as a result of exposure to cigarette smoke or use of tobacco products or as a result of the release of inflammatory mediators (NIH, 2001).

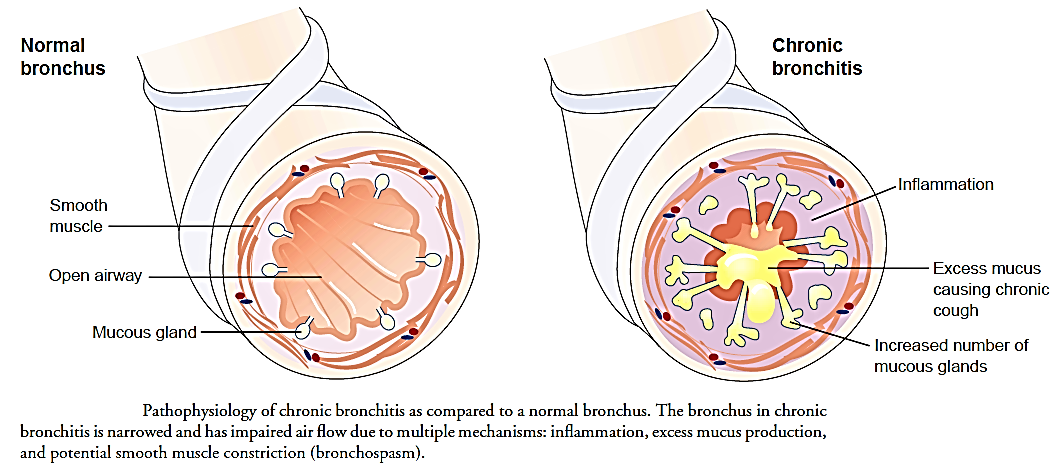

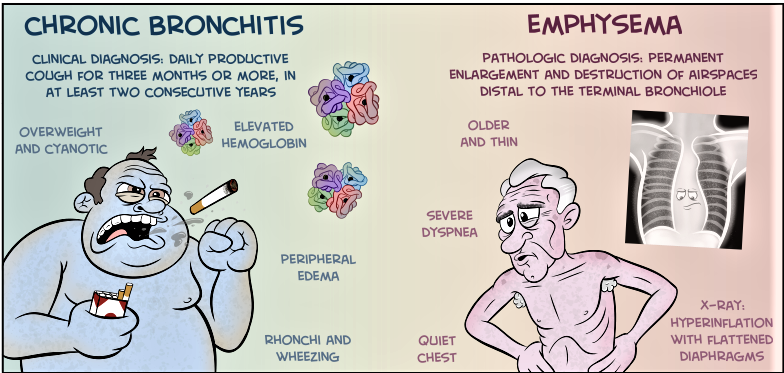

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis, a disease of the airways, is defined as the presence of cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years. In many cases, smoke or other environmental pollutants irritate the airways, resulting in hypersecretion of mucus and inflammation. This constant irritation causes the mucus-secreting glands and goblet cells to increase in number, ciliary function is reduced, and more mucus is produced. The bronchial walls become thickened, the bronchial lumen is narrowed, and mucus may plug the airway. Alveoli adjacent to the bronchioles may become damaged and fibrosed, resulting in altered function of the alveolar macrophages. This is significant because the macrophages play an important role in destroying foreign particles, including bacteria. As a result, the patient becomes more susceptible to respiratory infection. A wide range of viral, bacterial, and mycoplasmal infections can produce acute episodes of bronchitis. Exacerbations of chronic bronchitis are most likely to occur during the winter.

Emphysema

In emphysema, impaired gas exchange (oxygen, carbon dioxide) results from destruction of the walls of overdistended alveoli. “Emphysema” is a pathological term that describes an abnormal distention of the air spaces beyond the terminal bronchioles, with destruction of the walls of the alveoli. It is the end stage of a process that has progressed slowly for many years. As the walls of the alveoli are destroyed (a process accelerated by recurrent infections), the alveolar surface area in direct contact with the pulmonary capillaries continually decreases, causing an increase in dead space (lung area where no gas exchange can occur) and impaired oxygen diffusion, which leads to hypoxemia. In the later stages of the disease, carbon dioxide elimination is impaired, resulting in increased carbon dioxide tension in arterial blood (hypercapnia) and causing respiratory acidosis. As the alveolar walls continue to break down, the pulmonary capillary bed is reduced.

Consequently, pulmonary blood flow is increased, forcing the right ventricle to maintain a higher blood pressure in the pulmonary artery. Hypoxemia may further increase pulmonary artery pressure. Thus, right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale) is one of the complications of emphysema. Congestion, dependent edema, distended neck veins, or pain in the region of the liver suggests the development of cardiac failure.

Risk Factors for COPD

- Exposure to tobacco smoke accounts for an estimated 80% to 90% of COPD cases (Rennard, 1998)

- Passive smoking

- Occupational exposure

- Ambient air pollution

- Genetic abnormalities, including a deficiency of alpha1-antitrypsin, an enzyme inhibitor that normally counteracts the destruction of lung tissue by certain other enzymes

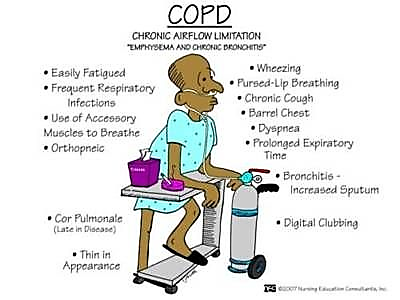

Clinical Manifestations

COPD is characterized by three primary symptoms:

- cough,

- sputum production, and

- dyspnea on exertion. These symptoms often worsen over time.

- Chronic cough and sputum production often precede the development of airflow limitation by many years. However, not all individuals with cough and sputum production will develop COPD.

- Dyspnea may be severe and often interferes with the patient’s activities.

- Weight loss is common because dyspnea interferes with eating, and the work of breathing is energy-depleting.

Often the patient cannot participate in even mild exercise because of dyspnea; as COPD progresses, dyspnea occurs even at rest. As the work of breathing increases over time, the accessory muscles are recruited in an effort to breathe. The patient with COPD is at risk for respiratory insufficiency and respiratory infections, which in turn increase the risk for acute and chronic respiratory failure.

- In COPD patients with a primary emphysematous component, chronic hyperinflation leads to the “barrel chest” thorax configuration. This results from fixation of the ribs in the inspiratory position (due to hyperinflation) and from loss of lung elasticity. Retraction of the supraclavicular fossae occurs on inspiration, causing the shoulders to heave upward. In advanced emphysema, the abdominal muscles also contract on inspiration.

Complications

There are two major life-threatening complications of COPD: respiratory insufficiency and failure.

- Respiratory failure. The acuity and the onset of respiratory failure depend on baseline pulmonary function, pulse oximetry or arterial blood gas values, comorbid conditions, and the severity of other complications of COPD.

- Respiratory insufficiency. This can be acute or chronic, and may necessitate ventilator support until other acute complications can be treated.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnosis and assessment of COPD must be done carefully since the three main symptoms are common among chronic pulmonary disorders.

- Health history. The nurse should obtain a thorough health history from patients with known or potential COPD.

- Pulmonary function studies. Pulmonary function studies are used to help confirm the diagnosis of COPD, determine disease severity, and monitor disease progression.

- Spirometry. Spirometry is used to evaluate airway obstruction, which is determined by the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity.

- ABG. Arterial blood gas measurement is used to assess baseline oxygenation and gas exchange and is especially important in advanced COPD.

- Chest x-ray. A chest x-ray may be obtained to exclude alternative diagnoses.

- CT scan. Computed tomography chest scan may help in the differential diagnosis.

- Screening for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Screening can be performed for patients younger than 45 years old and for those with a strong family history of COPD.

- Chest x-ray: May reveal hyperinflation of lungs, flattened diaphragm, increased retrosternal air space, decreased vascular markings/bullae (emphysema), increased bronchovascular markings (bronchitis), normal findings during periods of remission (asthma).

- Pulmonary function tests: Done to determine cause of dyspnea, whether functional abnormality is obstructive or restrictive, to estimate degree of dysfunction and to evaluate effects of therapy, e.g., bronchodilators. Exercise pulmonary function studies may also be done to evaluate activity tolerance in those with known pulmonary impairment/progression of disease.

- The forced expiratory volume over 1 second (FEV1): Reduced FEV1 not only is the standard way of assessing the clinical course and degree of reversibility in response to therapy, but also is an important predictor of prognosis.

- Total lung capacity (TLC), functional residual capacity (FRC), and residual volume (RV): May be increased, indicating air-trapping. In obstructive lung disease, the RV will make up the greater portion of the TLC.

- Arterial blood gases (ABGs): Determines degree and severity of disease process, e.g., most often Pao2is decreased, and Paco2 is normal or increased in chronic bronchitis and emphysema, but is often decreased in asthma; pH normal or acidotic, mild respiratory alkalosis secondary to hyperventilation (moderate emphysema or asthma).

- DL CO test: Assesses diffusion in lungs. Carbon monoxide is used to measure gas diffusion across the alveocapillary membrane. Because carbon monoxide combines with hemoglobin 200 times more easily than oxygen, it easily affects the alveoli and small airways where gas exchange occurs. Emphysema is the only obstructive disease that causes diffusion dysfunction.

- Bronchogram: Can show cylindrical dilation of bronchi on inspiration; bronchial collapse on forced expiration (emphysema); enlarged mucous ducts (bronchitis).

- Lung scan: Perfusion/ventilation studies may be done to differentiate between the various pulmonary diseases. COPD is characterized by a mismatch of perfusion and ventilation (i.e., areas of abnormal ventilation in area of perfusion defect).

- Complete blood count (CBC) and differential: Increased hemoglobin (advanced emphysema), increased eosinophils (asthma).

- Blood chemistry: alpha1-antitrypsin is measured to verify deficiency and diagnosis of primary emphysema.

- Sputum culture: Determines presence of infection, identifies pathogen.

- Cytologic examination: Rules out underlying malignancy or allergic disorder.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Right axis deviation, peaked P waves (severe asthma); atrial dysrhythmias (bronchitis), tall, peaked P waves in leads II, III, AVF (bronchitis, emphysema); vertical QRS axis (emphysema).

- Exercise ECG, stress test: Helps in assessing degree of pulmonary dysfunction, evaluating effectiveness of bronchodilator therapy, planning/evaluating exercise program.

Medical Management

Healthcare providers perform medical management by considering the assessment data first and matching the appropriate intervention to the existing manifestation.

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Bronchodilators. Bronchodilators relieve bronchospasm by altering the smooth muscle tone and reduce airway obstruction by allowing increased oxygen distribution throughout the lungs and improving alveolar ventilation.

- Corticosteroids. A short trial course of oral corticosteroids may be prescribed for patients to determine whether pulmonary function improves and symptoms decrease.

- Other medications. Other pharmacologic treatments that may be used in COPD include alpha1-antitrypsin augmentation therapy, antibiotic agents, mucolytic agents, antitussive agents, vasodilators, and narcotics.

Management of Exacerbations

- Optimization of bronchodilator medications is first-line therapy and involves identifying the best medications or combinations of medications taken on a regular schedule for a specific patient.

- Hospitalization. Indications for hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD include severe dyspnea that does not respond to initial therapy, confusion or lethargy, respiratory muscle fatigue, paradoxical chest wall movement, and peripheral edema.

- Oxygen therapy. Upon arrival of the patient in the emergency room, supplemental oxygen therapy is administered and rapid assessment is performed to determine if the exacerbation is life-threatening.

- Antibiotics. Antibiotics have been shown to be of some benefit to patients with increased dyspnea, increased sputum production, and increased sputum purulence.

Surgical Management

Patients with COPD also have options for surgery to improve their condition.

- Bullectomy. Bullectomy is a surgical option for select patients with bullous emphysema and can help reduce dyspnea and improve lung function.

- Lung Volume Reduction Surgery. Lung volume reduction surgery is a palliative surgery in patients with homogenous disease or disease that is focused in one area and not widespread throughout the lungs.

- Lung Transplantation. Lung transplantation is a viable option for definitive surgical treatment of end-stage emphysema.

Nursing Management

Management of patients with COPD should be incorporated with teaching and improving the respiratory status of the patient.

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of the respiratory system should be done rapidly yet accurately.

- Assess patient’s exposure to risk factors.

- Assess the patient’s past and present medical history.

- Assess the signs and symptoms of COPD and their severity.

- Assess the patient’s knowledge of the disease.

- Assess the patient’s vital signs.

- Assess breath sounds and pattern.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of COPD would mainly depend on the assessment data gathered by the healthcare team members.

- Impaired gas exchange due to chronic inhalation of toxins.

- Ineffective airway clearance related to bronchoconstriction, increased mucus production, ineffective cough, and other complications.

- Ineffective breathing pattern related to shortness of breath, mucus, bronchoconstriction, and airway irritants.

- Self-care deficit related to fatigue.

- Activity intolerance related to hypoxemia and ineffective breathing patterns.

Planning & Goals

Goals to achieve in patients with COPD include:

- Improvement in gas exchange.

- Achievement of airway clearance.

- Improvement in breathing pattern.

- Independence in self-care activities.

- Improvement in activity intolerance.

- Ventilation/oxygenation adequate to meet self-care needs.

- Nutritional intake meeting caloric needs.

- Infection treated/prevented.

- Disease process/prognosis and therapeutic regimen understood.

- Plan in place to meet needs after discharge.

Nursing Priorities

- Maintain airway patency.

- Assist with measures to facilitate gas exchange.

- Enhance nutritional intake.

- Prevent complications, slow progression of condition.

- Provide information about disease process/prognosis and treatment regimen.

Nursing Interventions

Patient and family teaching is an important nursing intervention to enhance self-management in patients with any chronic pulmonary disorder.

To achieve airway clearance:

- The nurse must appropriately administer bronchodilators and corticosteroids and become alert for potential side effects.

- Direct or controlled coughing. The nurse instructs the patient in direct or controlled coughing, which is more effective and reduces fatigue associated with undirected forceful coughing.

To improve breathing pattern:

- Inspiratory muscle training. This may help improve the breathing pattern.

- Diaphragmatic breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing reduces respiratory rate, increases alveolar ventilation, and sometimes helps expel as much air as possible during expiration.

- Pursed lip breathing. Pursed lip breathing helps slow expiration, prevents collapse of small airways, and control the rate and depth of respiration.

To improve activity intolerance:

- Manage daily activities. Daily activities must be paced throughout the day and support devices can be also used to decrease energy expenditure.

- Exercise training. Exercise training can help strengthen muscles of the upper and lower extremities and improve exercise tolerance and endurance.

- Walking aids. Use of walking aids may be recommended to improve activity levels and ambulation.

To monitor and manage potential complications:

- Monitor cognitive changes. The nurse should monitor for cognitive changes such as personality and behavior changes and memory impairment.

- Monitor pulse oximetry values. Pulse oximetry values are used to assess the patient’s need for oxygen and administer supplemental oxygen as prescribed.

- Prevent infection. The nurse should encourage the patient to be immunized against influenza and S. pneumonia because the patient is prone to respiratory infection.

Evaluation

During evaluation, the effectiveness of the care plan would be measured if goals were achieved in the end and the patient:

- Identifies the hazards of cigarette smoking.

- Identifies resources for smoking cessation.

- Enrolls in smoking cessation program.

- Minimizes or eliminates exposures.

- Verbalizes the need for fluids.

- Is free of infection.

- Practices breathing techniques.

- Performs activities with less shortness of breath.

Discharge and Home Care Guidelines

It is important for the nurse to assess the knowledge of patient and family members about self-care and the therapeutic regimen.

- Setting goals. If the COPD is mild, the objectives of the treatment are to increase exercise tolerance and prevent further loss of pulmonary function, while if COPD is severe, these objectives are to preserve current pulmonary function and relieve symptoms as much as possible.

- Temperature control. The nurse should instruct the patient to avoid extremes of heat and cold because heat increases the temperature and thereby raising oxygen requirements and high altitudes increase hypoxemia.

- Activity moderation. The patient should adapt a lifestyle of moderate activity and should avoid emotional disturbances and stressful situations that might trigger a coughing episode.

- Breathing retraining. The home care nurse must provide the education and breathing retraining necessary to optimize the patient’s functional status.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation is an essential part of the patient’s chart because the interventions and medications given and done are reflected on this part.

- Document assessment findings including respiratory rate, character of breath sounds; frequency, amount and appearance of secretions laboratory findings and mentation level.

- Document conditions that interfere with oxygen supply.

- Document plan of care and specific interventions.

- Document liters of supplemental oxygen.

- Document client’s responses to treatment, teaching, and actions performed.

- Document teaching plan.

- Document modifications to plan of care.

- Document attainment or progress towards goals.

I must thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this site. Wenda Nicholas Medwin

I visited several blogs however the audio feature for audio songs existing at this web site is actually marvelous. Mirelle Wood Ciaphus

Thank you for sharing your info. I really appreciate your efforts and I am waiting for your next post thanks once again. Fulvia Hardy Scevor