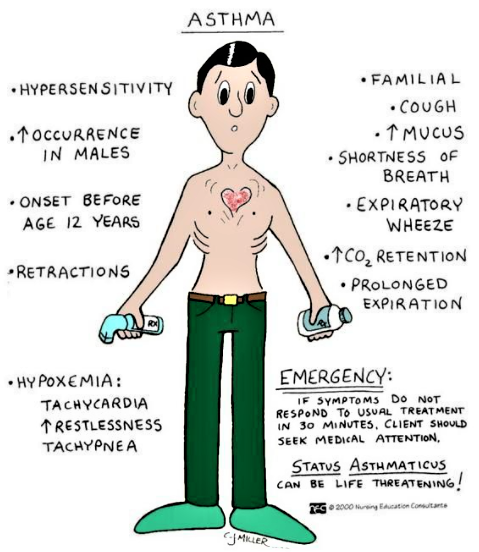

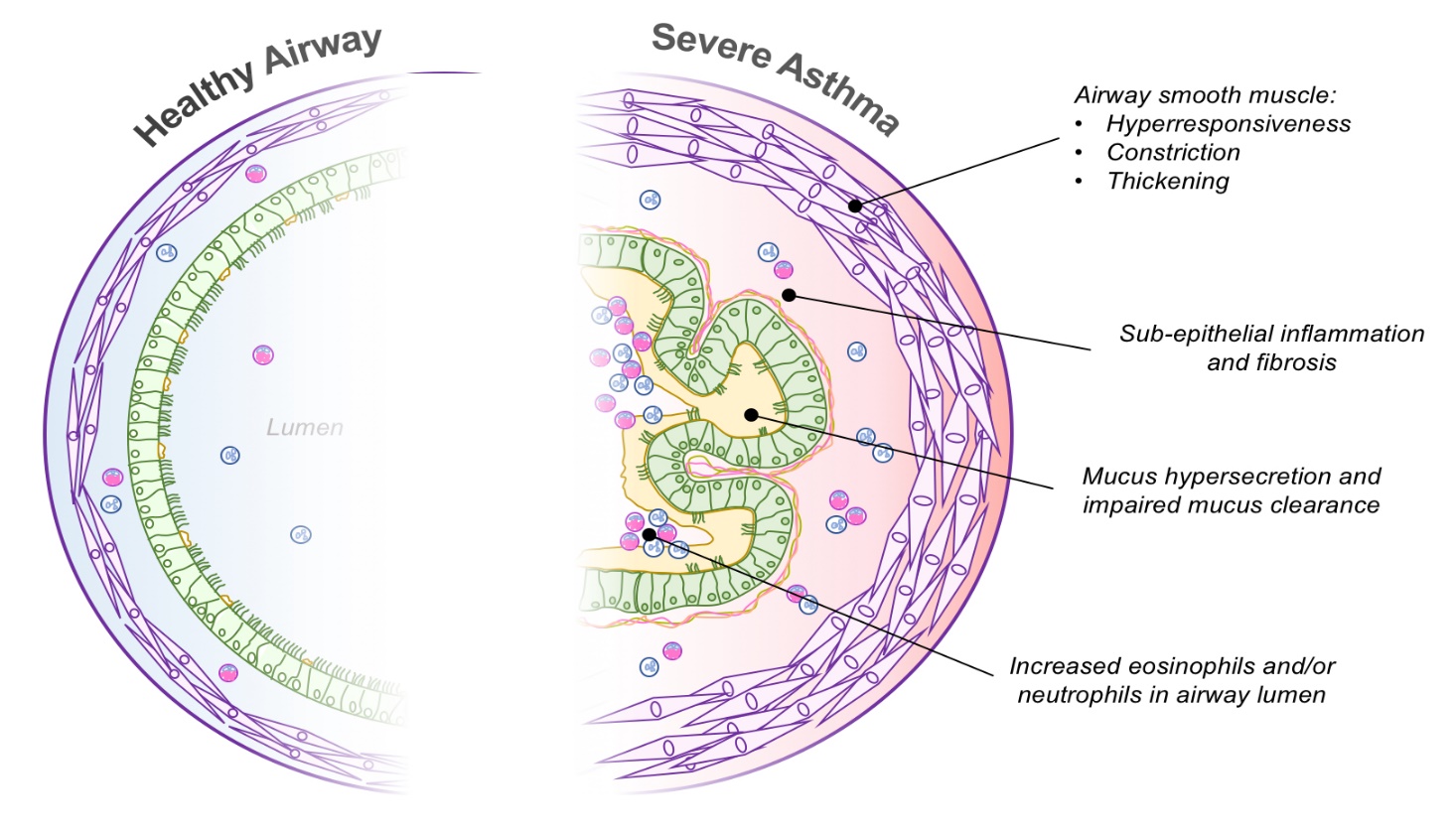

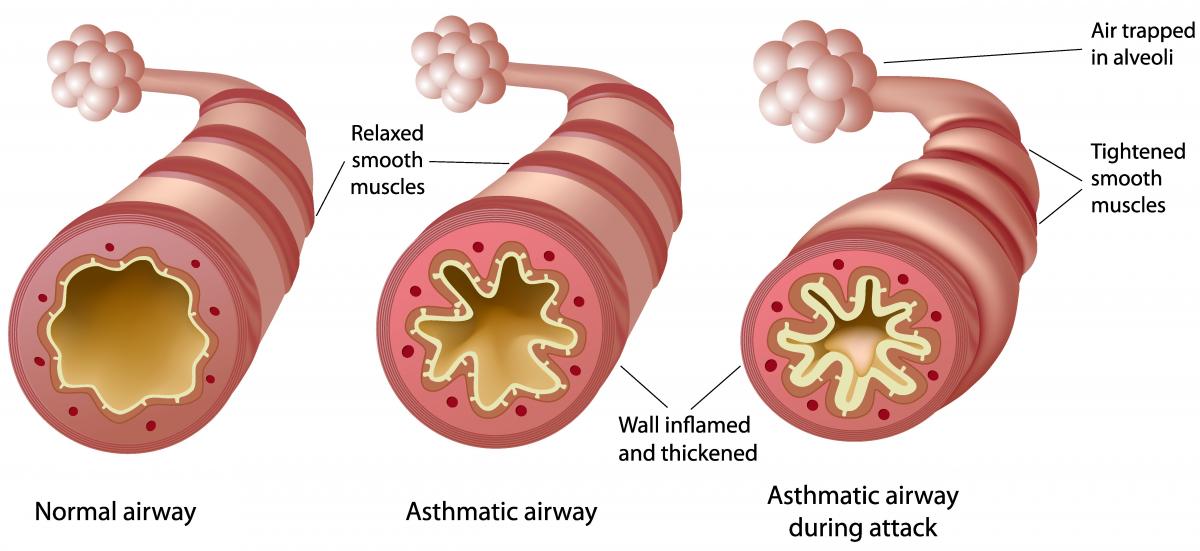

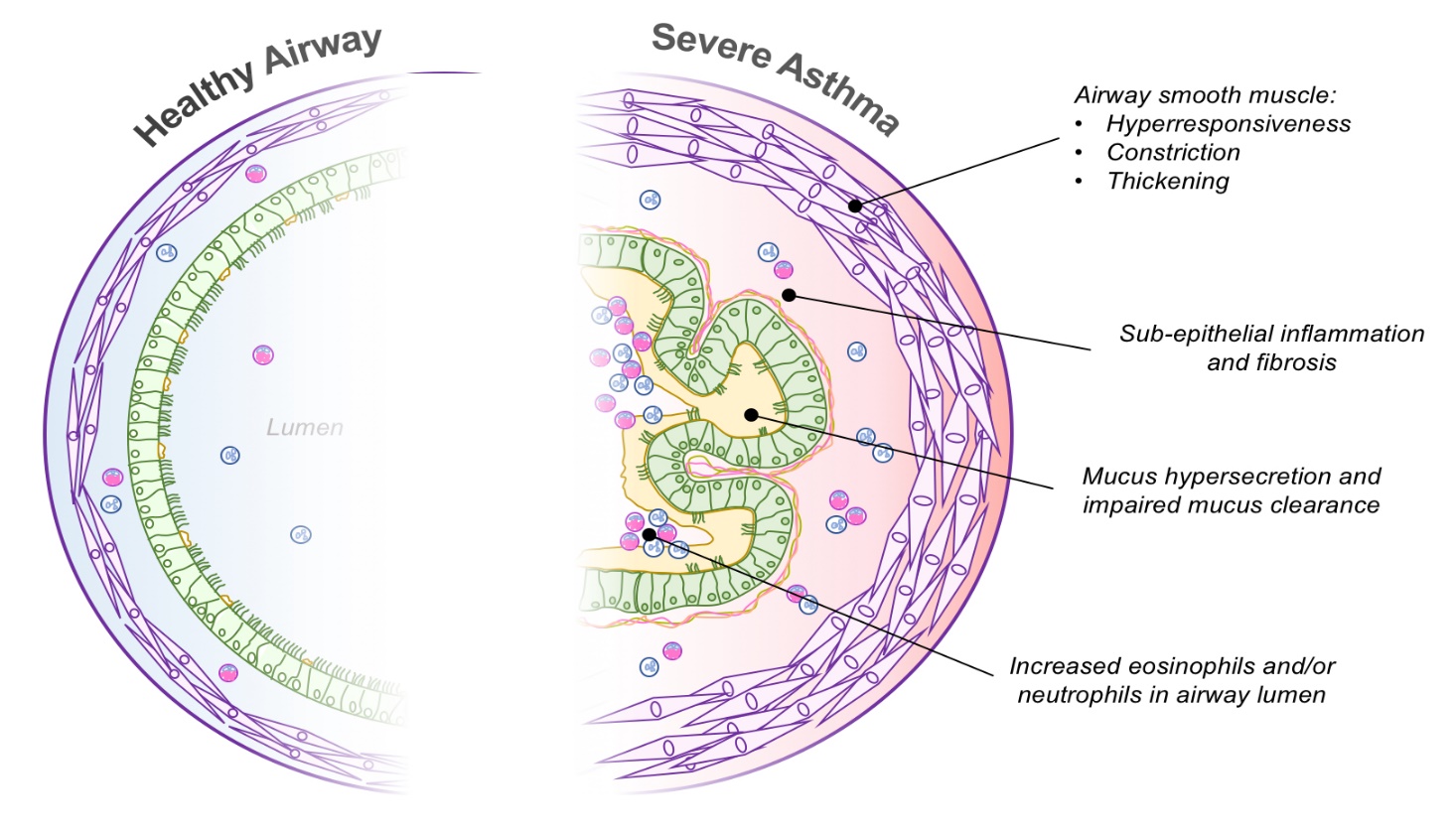

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways associated with airway hyperresponsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing. These episodes are usually associated with airflow obstruction within the lung, often reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment.

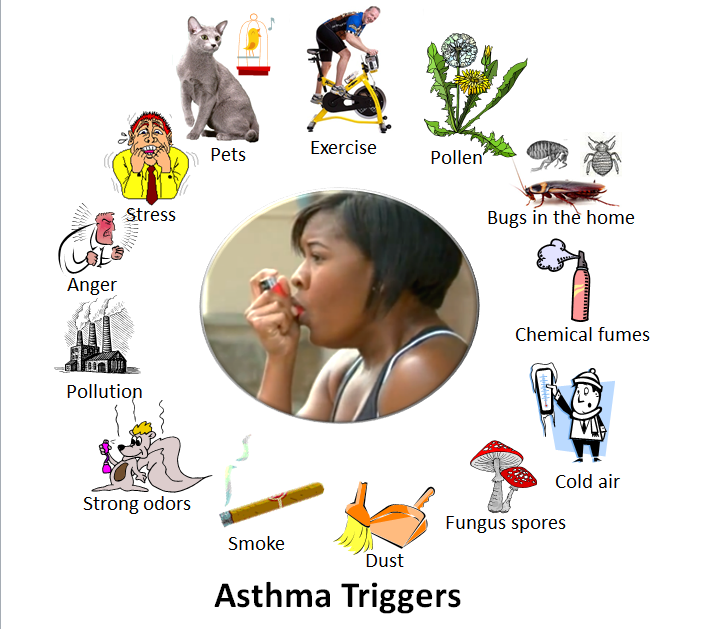

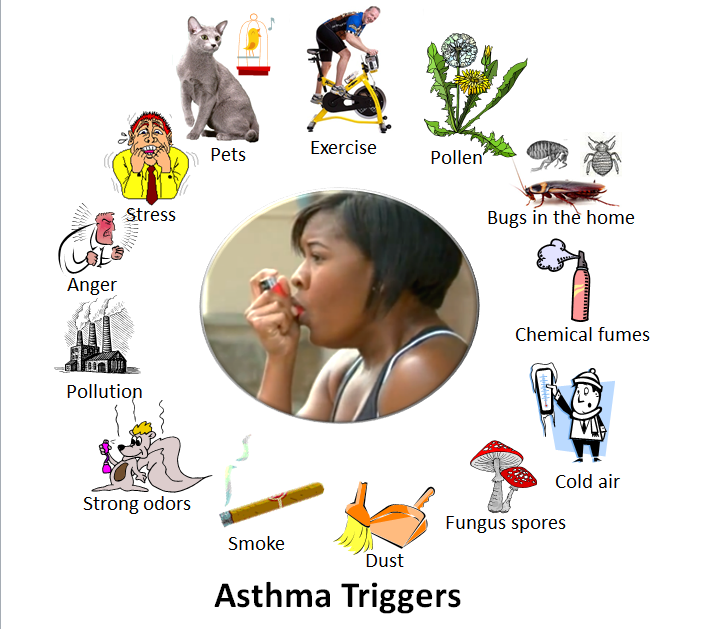

Factors that precipitate/aggravate asthma include: allergens, infection, exercise, drugs (aspirin), tobacco, etc.

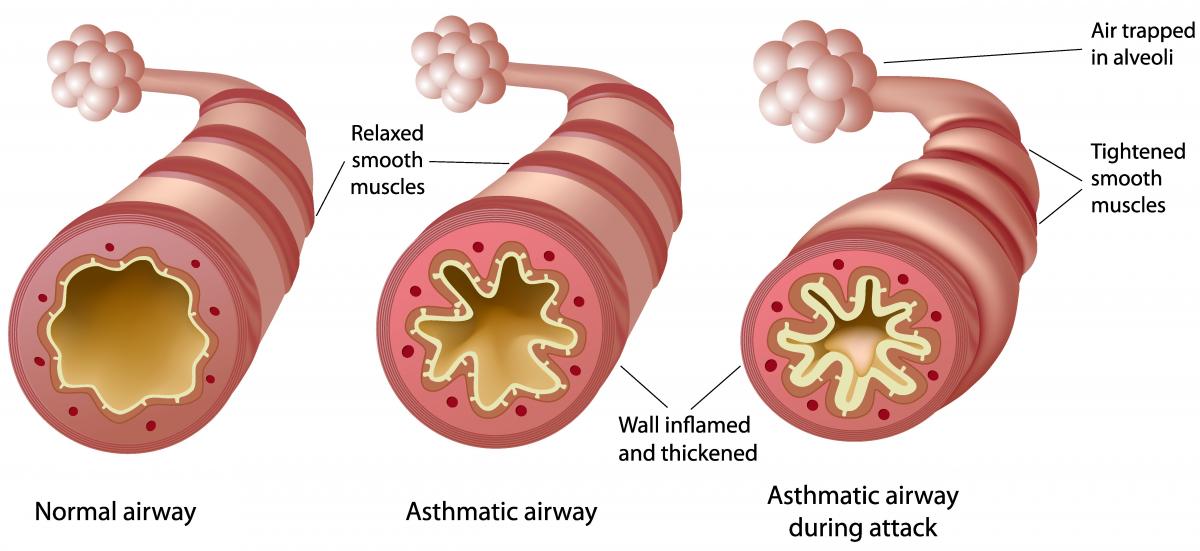

Pathophysiology:-

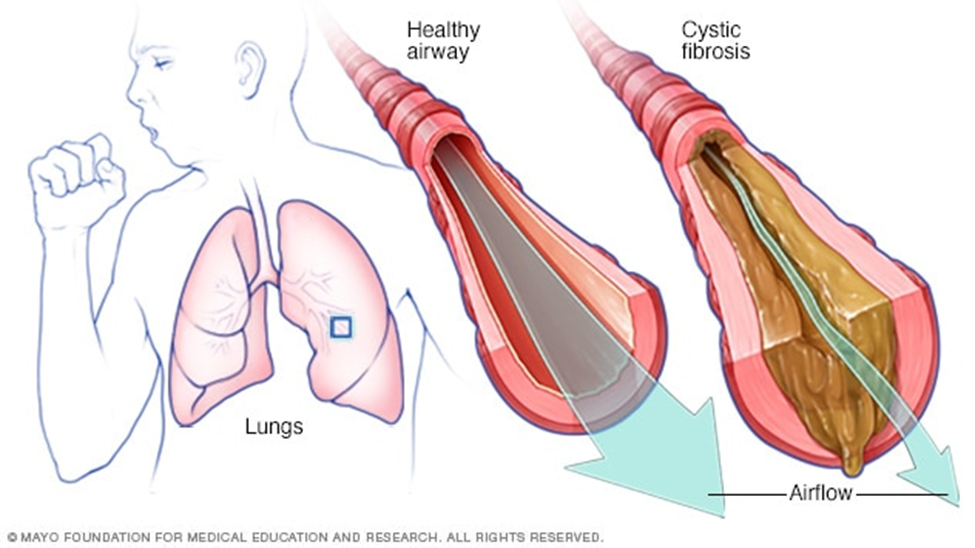

Airway inflammation is the primary problem in asthma. An initial event in asthma appears to be the release of inflammatory mediators triggered. The mediators are released from bronchial mast cells, alveolar macrophages, and epithelial cells. Some mediators directly cause acute bronchoconstriction.” The inflammatory mediators also direct the activation of eosinophils and neutrophils, and their migration to the airways, where they cause injury Called “late-phase asthmatic response” results in epithelial damage, airway edema, mucus hypersecretion and hyper responsiveness of bronchial smooth muscle varying airflow obstruction leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough.

Causes/Triggers of Asthma:

The exact causes of asthma are still unknown but we do know that children are more likely to have asthma if other members of the family also have it. Related conditions like hay fever, eczema or food allergies can also increase the risk of asthma.

Smoking during pregnancy or exposing a child to tobacco smoke will increase their risk of developing asthma. Being overweight also increases the risk of developing asthma.

Smoking during pregnancy or exposing a child to tobacco smoke will increase their risk of developing asthma. Being overweight also increases the risk of developing asthma.

Though some children lose their symptoms as they grow older, asthma is a chronic disease so symptoms may come back later in life.

- Asthma is a breathing disease which is triggered by various allergies and substance, like:

- polluted matters, smoking, animal products and many more.

- Asthma problems can be caused by different foods which can react on the immune system of the body. Some people have allergy with particular food and various symptoms are appeared in your body like swelling, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, wheezing and breathing problems. The use of foods like peanuts, shellfish, eggs, various dairy products can be harmful for the patients so they should avoid all these foods. All such foods and wine containing histamine can cause development in asthma.

- The fizzy drinks, prepared salads and meats, home brewed beer and wine can contain the allergic reaction. If you have some problems of allergy, then you should contact with specialist for the allergic problems. The women can face the asthma problems during their periods, pregnancy, puberty and menopause.

The following things can trigger an asthma attack:

- Colds and Viral Infections

- House Dust Mites

- Fur and dander from pets

- Changes in weather, and cold air

- Pollen

- Tobacco smoke and pollution

- Mould

- Chemicals

- Allergies

- Exercise

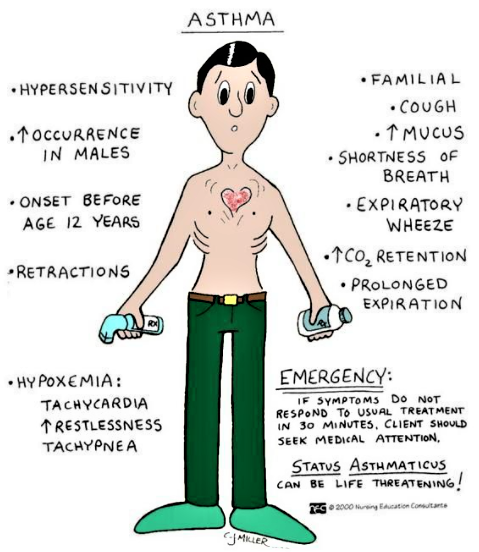

Clinical Manifestations

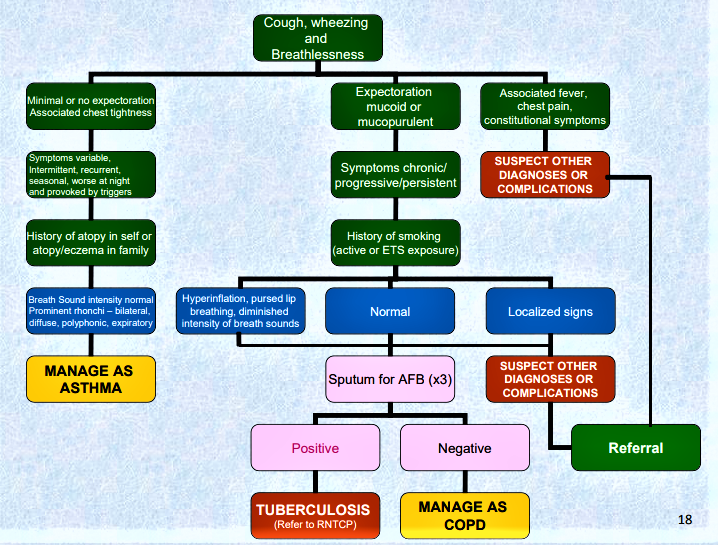

The three most common symptoms of asthma are cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. In some instances, cough may be the only symptom. Asthma attacks often occur at night or early in the morning, possibly due to circadian variations that influence airway receptor thresholds.

- Cough. There are instances that cough is the only symptom.

- Dyspnea. General tightness may occur which leads to dyspnea.

- Wheezing. There may be wheezing, first on expiration, and then possibly during inspiration as well.

- Asthma attacks frequently occur at night or in the early morning.

- An asthma exacerbation is frequently preceded by increasing symptoms over days, but it may begin abruptly.

- Expiration requires effort and becomes prolonged.

- As exacerbation progresses, central cyanosis secondary to severe hypoxia may occur.

- Additional symptoms, such as diaphoresis, tachycardia, and a widened pulse pressure, may occur.

- Exercise-induced asthma: maximal symptoms during exercise, absence of nocturnal symptoms, and sometimes only a description of a “choking” sensation during exercise.

- A severe, continuous reaction, status asthmaticus, may occur. It is life-threatening.

- Eczema, rashes, and temporary edema are allergic reactions that may be noted with asthma.

Assessment of the severity of asthma attack

- The severity of the asthma attack must be rapidly evaluated by the following clinical criteria. Not all signs are necessarily present.

Assessment of severity in children over 2 years and adults

| Mild to moderate attack |

Severe attack |

Life threatening attack |

| to talk in sentences

Respiratory rate (RR)

Children 2-5 years ≤ 40/ minute

Children > 5 years ≤ 30/ minute

Heart rate

Children 2-5 years ≤ 140/ minute

Children > 5 years ≤ 125/ minute

and

No criteria of severity |

Cannot complete sentences in one breath

or

Too breathless to talk or feed

RR

Children 2-5 years > 40/minute

Children > 5 years > 30/minute

Adults ≥ 25/minute

Heart rate

Children 2-5 years > 140/minute

Children > 5 years > 125/minute

Adults ≥ 110/minute

SpO2 ≥ 92% |

Altered level of consciousness

(drowsiness, confusion, coma)

Exhaustion

Silent chest

Paradoxical thoracoabdominal movement

Cyanosis

Collapse

Bradycardia in children or arrhythmia/ hypotension in adults

SpO2 < 92% |

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A complete family, environmental, and occupational history is essential.

- Positive family history. Asthma is a hereditary disease, and can be possibly acquired by any member of the family who has asthma within their clan.

- Environmental factors. Seasonal changes, high pollen counts, mold, pet dander, climate changes, and air pollution are primarily associated with asthma.

- Comorbid conditions. Comorbid conditions that may accompany asthma may include gastroeasophageal reflux, drug-induced asthma, and allergic broncopulmonary aspergillosis.

Complications

Complications of asthma may include status asthmaticus, respiratoryfailure, pneumonia, and atelectasis. Airway obstruction, particularly during acute asthmatic episodes, often results in hypoxemia, requiring the administration of oxygen and the monitoring of pulse oximetry and arterial blood gases. Fluids are administered because people with asthma are frequently dehydrated from diaphoresis and insensible fluid loss with hyperventilation.

Medical Management

Immediate intervention is necessary because the continuing and progressive dyspnea leads to increased anxiety, aggravating the situation.

Goals of Asthma Therapy

- Prevent recurrent exacerbations and minimize the need for emergency department visits or hospitalizations

- Maintain (near‐) “normal” pulmonary function

- Maintain normal activity levels (including exercise and other physical activity)

- Provide optimal pharmacotherapy with minimal or no adverse effects

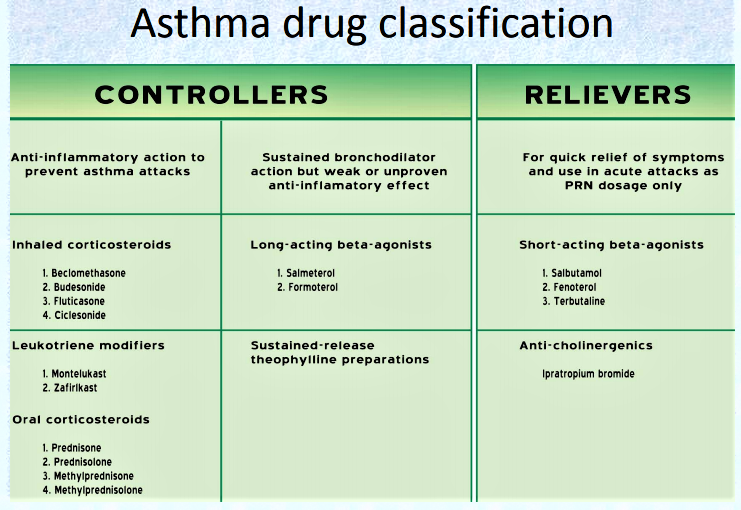

Pharmacologic Therapy

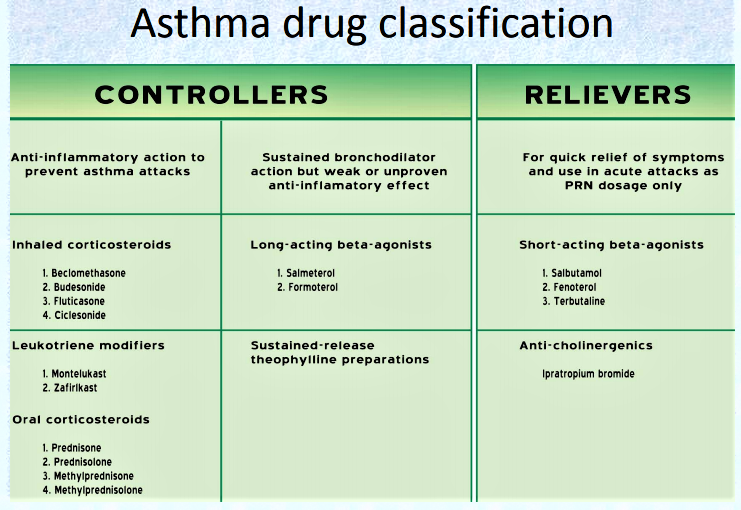

There are two classes of medications—long-acting control and quick-relief medications—as well as combination products.

- Short-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists

- Anticholinergics

- •Corticosteroids: metered-dose inhaler (MDI)

- Leukotriene modifiers inhibitors/antileukotrienes

- Methylxanthines

Mild to moderate attack

– Reassure the patient; place him in a 1/2 sitting position.

– Administer:

• salbutamol (aerosol): 2 to 4 puffs every 20 to 30 minutes, up to 10 puffs if necessary during the first hour. In children, use a spacer 1to ease administration (use face mask in children under 3 years).

Single puffs should be given one at a time, let the child breathe 4 to 5 times from the spacer before repeating the procedure.

• prednisolone PO: one dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg

– If the attack is completely resolved: observe the patient for 1 hour (4 hours if he lives far from the health centre) then give outpatient treatment: salbutamol for 24 to 48 hours (2 to 4 puffs every 4 to 6 hours depending on clinical evolution) and prednisolone PO (1 to 2 mg/kg once daily) to complete 3 days of treatment.

– If the attack is only partially resolved, continue with salbutamol 2 to 4 puffs every 3 to 4 hours if the attack is mild; 6 puffs every 1 to 2 hours if the attack is moderate, until symptoms subside, then when the attack is completely resolved, proceed as above.

– If symptoms worsen or do not improve, treat as sever attack.

Severe attack

– Hospitalise the patient; place him in a 1/2 sitting position.

– Administer:

• oxygen continuously, at least 5 litres/minute or maintain the SpO2 between 94 and 98%.

• salbutamol (aerosol): 2 to 4 puffs every 20 to 30 minutes, up to 10 puffs if necessary in children under 5 years, up to 20 puffs in children over 5 years and adults. Use a spacer to increase effectiveness, irrespective of age.

or salbutamol (solution for nebulisation), see Life-threatening attack

• prednisolone PO: one dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg

In the case of vomiting, until the patient can tolerate oral prednisolone, use hydrocortisone IV:

Children 1 month to < 5 years: 4 mg/kg every 6 hours (max. 100 mg per dose)

Children 5 years and over and adults: 100 mg every 6 hours

– If the attack is completely resolved, observe the patient for at least 4 hours. Continue the treatment with salbutamol for 24 to 48 hours (2 to 4 puffs every 4 hours) and prednisolone PO (1 to 2 mg/kg once daily) to complete 3 days of treatment.

Reassess after 10 days: consider long-term treatment if the asthma attacks have been occurring for several months. If the patient is already receiving long-term treatment, reassess the severity of the asthma (see table) and review compliance and correct use of medication and adjust treatment if necessary.

– If symptoms worsen or do not improve, see Life-threatening attack.

Life-threatening attack (intensive care)

– Insert an IV line.

– Administer:

• oxygen continuously, at least 5 litres/minute or maintain the SpO2 between 94 and 98%.

• salbutamol + ipratropium nebuliser solutions using a nebuliser:

| Children 1 month to < 5 years |

salbutamol 2.5 mg + ipratropium 0.25 mg every 20 to 30 minutes |

| Children 5 to < 12 years |

salbutamol 2.5 to 5 mg + ipratropium 0.25 mg every 20 to 30 minutes |

| Children 12 years and over and adults |

salbutamol 5 mg + ipratropium 0.5 mg every 20 to 30 minutes |

The two solutions can be mixed in the nebuliser reservoir.

• corticosteriods (prednisolone PO or hydrocortisone IV) as for severe attack

– If the attack is resolved after one hour: switch to salbutamol aerosol and continue prednisolone PO as for severe attack

– If symptoms do not improve after one hour:

• administer a single dose of magnesium sulfate by IV infusion in 0.9% sodium chloride over 20 minutes, monitoring blood pressure:

Children over 2 years: 40 mg/kg

Adults: 1 to 2 g

• continue salbutamol by nebulisation and corticosteriods, as above.

Notes:

– In pregnant women, treatment is the same as for adults. In mild or moderate asthma attacks, administering oxygen reduces the risk of foetal hypoxia.

– For all patients, irrespective of the severity of the asthma attack, look for underlying lung infection and treat accordingly.

If a conventional spacer is not available, use a 500 ml plastic bottle: insert the mouthpiece of the inhaler into a hole made in the bottom of the bottle (the seal should be as tight as possible). The child breathes from the mouth of the bottle in the same way as he would with a spacer. The use of a plastic cup instead of a spacer is not recommended (ineffective).

Nursing Management

The immediate nursing care of patients with asthma depends on the severity of symptoms. The patient and family are often frightened and anxious because of the patient’s dyspnea.

Therefore, a calm approach is an important aspect of care.

- Assess the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of symptoms, breath sounds, peak flow, pulse oximetry, and vital signs.

- Obtain a history of allergic reactions to medications before administering medications.

- Identify medications the patient is currently taking.

- Administer medications as prescribed and monitor the patient’s responses to those medications; medications may include an antibiotic if the patient has an underlying respiratory infection.

- Administer fluids if the patient is dehydrated.

- Assist with intubation procedure, if required.

Promoting Home- and Community-Based Care

Teaching Patients Self-Care

- Teach patient and family about asthma (chronic inflammatory), purpose and action of medications, triggers to avoid and how to do so, and proper inhalation technique.

- Instruct patient and family about peak-flow monitoring.

- Teach patient how to implement an action plan and how and when to seek assistance.

- Obtain current educational materials for the patient based on the patient’s diagnosis, causative factors, educational level, and cultural background.

Continuing Care

- Emphasize adherence to prescribed therapy, preventive measures, and need for follow-up appointments.

- Refer for home health nurse as indicated.

- Home visit to assess for allergens may be indicated (with recurrent exacerbations).

- Refer patient to community support groups.

- Remind patients and families about the importance of health promotion strategies and recommended health screening.

Smoking during pregnancy or exposing a child to tobacco smoke will increase their risk of developing asthma. Being overweight also increases the risk of developing asthma.

Smoking during pregnancy or exposing a child to tobacco smoke will increase their risk of developing asthma. Being overweight also increases the risk of developing asthma.